A

Closed Mouth Doesn't Get Fed: Talking About Parent Involvement

BY RICHARD

A. GADSBY

Teacher’s

Network Leadership Institute

June 2005

RATIONALE

There is an old,

wise African proverb that states, “It takes a village to raise

a child” that is quoted often by educators. I believe it takes

three essential elements to fully educate a child – the school

fulfilling its obligations, the family fulfilling their obligations

and the child doing his/her part. Given some of the serious problems

facing education today, there is plenty of blame to go around. As

a teacher, one justification for lagging student achievement that

I hear frequently is that the parents are not involved in their children’s

education. To avoid unfairly placing blame in any situation, self-introspection

is a useful tool. In an examination of ourselves, administrators and

teachers must ask whether we are doing enough to involve parents in

our schools. The answer is, often, we are not.

The question

I chose for my research is: what is the impact of increased parent-teacher

contact on parental involvement and student achievement? My goal was

to measure the level of involvement of the parents of my students

and to experiment with several methods of increasing my communication

with them to test whether it would spur greater involvement on their

part.

My research is

composed of a collection of data regarding parent involvement. It

is based on surveys and notes of communication with both parents and

students in my classroom. I utilized several research methods for

communicating with parents, all aimed at increasing their involvement.

These included letters, direct contact in person or by telephone,

and electronic communication. I also performed a case study of one

student who experienced a substantial change in his family’s

involvement during the school year. My analysis of my findings focuses

on the relative success of these methods in affecting levels of parental

involvement and the reactions of parents and students to these methods.

This analysis leads to several policy recommendations for changes

in parent communication strategies to be instituted on the classroom,

school and district levels.

BACKGROUND

I teach an eighth

grade Social Studies curriculum to four classes of approximately twenty-two

students each. My school is a Grade 6-8 middle school in the Fort

Greene section of Brooklyn, NY, a largely middle class integrated

community. Our school serves children of color almost exclusively,

the majority of who are 2nd – 3rd generation immigrants. The

demographics of the school are approximately eighty-seven percent

African-American, ten percent Latino and three percent Asian, White

or other. Practically 100% of our students qualify for free lunch

under the federal ‘Title I’ program.

My school currently

has approximately 45% of our students performing at or better than

grade level (Level 3) on the New York State Reading and Mathematics

Assessment Exams, which is fairly high percentage in comparison to

other New York City area middle schools. Despite these Reading and

Mathematics scores, in recent years we have found that many of our

students’ academic performance in their core content subjects

(Math, English Language Arts, Social Studies and Science) is below

the level that would be expected based on their test scores. Specifically,

we have seen high numbers of failing students and high summer school

attendance rates. For the past 3 academic years we have had approximately

20% of our graduating Eighth-graders attend summer school. Despite

numerous and varied programs and strategies to improve academic performance,

we have been unable to achieve any significant or sustained decrease

in these numbers. (Note: for the current academic year, the percentage

of students attending summer school has decreased to approximately

15%).

At the same time,

we have one academic program that is dedicated to an accelerated curriculum

of courses, including Regents-level Math, Science and Spanish classes.

The students in this program have achieved a much higher level of

academic success on their core content classes than the rest of the

student body, while having only slightly higher results on the state

standardized exams. Parents of these children are required to sign

a contract upon admission to the program requiring them to maintain

an academic average of 80% or better for each academic marking period.

Or face removal from the program. We feel that this commitment on

the part of the parents is a key element to the success of the sub-school.

As a school community,

we have determined that in order to improve our students’ performance,

increased involvement from our parents is a necessity. Like many schools

today, we have struggled to achieve what we would consider an acceptable

level of parental participation in school affairs. We have tried several

methods to increase involvement, such as rescheduling our PTA meetings

to Saturday mornings, which have had some limited success. Our challenge

has been convincing parents that it is necessary to sustain a high

level of involvement at the middle school level. Thus, our goal over

this time period has been to increase the involvement of parents in

the school community, focusing on Parent-Teacher Association (“PTA”)

participation and teacher contact to levels generally demonstrated

in elementary schools.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Despite the significant

number and scope of reforms that instructional theory and methods

have undergone in the last 20 years, many researchers find that student

performance has not undergone a significant improvement. They theorize

that one of the contributing factors to this statistic is the fact

that students are most influenced by their experiences in the time

that they spend outside of school, mainly with their families. (Henderson,

A.T. and Berla, N., A New Generation of Evidence: The Family is

Critical to Student Achievement. Washington, D.C., National Committee

for Citizens in Education). While school support of students is a

key component of improving underachieving schools, another essential

component is cooperation and assistance from families in overseeing

the education of their children. (Sanders, Mavis and Epstein, Joyce

(1998), School-Family-Community Partnerships in Middle and High

Schools. Center for Research on the Education of Students Placed

At Risk.)

Recent research

has found that as many as 1 in 3 middle school students report that

their parents have no idea how they are performing in school. Additionally,

1 in 6 students report that they believe their parents do not care

how they perform in school (Steinberg, Laurence, 1996, Beyond

the Classroom: Why School Reform has Failed and What Parents Need

to Do. New York: Simon & Schuster). These conclusions are

supported by the fact that parental involvement is normally at its

highest levels during the elementary school years, generally decreasing

as children reach the middle school and high school years. (Sanders

and Epstein, 1998).

The large body

of research on the importance of parental involvement overwhelmingly

supports the conclusion that parents are the strongest influence on

student academic success. Increased involvement by parents leads to

higher grades and scores on standardized examinations. (Bogenschneider,

Karen and Johnson, Carol, 2004, Family Involvement in Education:

How Important Is It? What Can Legislators Do?). The involvement

may take different forms, with each having a varying level of impact

on student achievement. Basic activities, such as assistance with

homework or otherwise helping the child learn at home, strongly correlate

with improved academic performance (Henderson, A.T. and Mapp, K.L.,

2002, A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact of School, Family and

Community Connections on Student Achievement. Austin, TX. National

Center for Family and Community Connections with Schools). Other research

has concluded that the parents’ physical presence at the school

for events such as PTA meetings can convey a message to students about

how seriously parents regard their academics (Steinberg, 1996).

While this involvement

has been found to be critical to students living in poverty or disadvantaged

situations, research has also concluded that the positive effects

of parental involvement stretch across varying socioeconomic backgrounds

and parents’ educational backgrounds: “Parental school

involvement had positive effects when parents had less than a high

school education or more than a college degree. What’s more,

the benefits held for Asian, Black, Hispanic and White teens in single-parent,

step-family or two-parent biological families” (Bogenschneider

and Johnson, 2004). Thus, the goal of maintaining a high level parental

involvement is important in all communities, not just urban or impoverished

communities, as many of today’s media outlets would suggest.

RESEARCH

TOOLS

I utilized three

main data collection tools in my study: surveys of students and parents

regarding levels of parent involvement, notes from communication with

parents throughout the year and anecdotal evidence from students concerning

their academics throughout the year, and an experiment with an Internet

website where I posted daily homework assignments that parents could

monitor.

Surveys

In order to gather information regarding the past and current involvement

levels of parents, I conducted separate surveys of my eighth-grade

students and their parents during the school year. The student surveys

addressed their assessment of their parents’ involvement level

in various categories throughout elementary school and middle school.

The parent survey was designed to discover the parents’ attitudes

about education in general and their perception of their level of

involvement.

Parent

Communication and Student Anecdotes

Throughout the academic year, I communicated with parents in a variety

of ways: an introductory letter at the beginning of the year outlining

the class expectations and need for parental involvement, the traditional

parent-teacher conferences, phone calls initiated by myself and parents,

and written progress reports that were distributed at the mid-point

of each marking period. I maintained informal notes on these communications

and used them to document the reactions of parents to information

about their children and reactions to questions or suggestions about

how they could take action to help them. I also questioned students

regarding their parents’ levels of involvement, their attitudes

about their grades and school in general. I recorded notes on some

of these informal conversations.

Homework

via the Internet

In response to parent concerns about their ability to regularly monitor

homework assignments, many teachers, including myself, posted our

daily assignments to an Internet webpage that could be accessed by

students and parents. I created a classroom homepage using an education

company’s website. The page was accessible through the company’s

website and also through a link contained on our school’s Internet

website. Students were given a letter to share with their parents

that contained the general information as well as classroom identification

and password. Updates and reminder notices were also distributed at

several other instances throughout the year.

DATA

Student

Surveys

My surveys of approximately 40 of my current Eighth-grade students

examined the students’ perception of their parents’ level

of involvement in their academics in elementary school compared to

their level of involvement during their middle school years. (See

Exhibit A) The measurement was based on several potential areas of

involvement, the most important of which were parental attendance

at PTA meetings and the frequency of parents checking the children’s

homework assignments. The students reported that in elementary school

47% of their parents attended PTA meetings frequently or occasionally

(minimum 2-3 meetings per year), while at the middle school level,

the percentage of parents attending meetings frequently or occasionally

decreased to 36%. Additionally, the percentage of parents who never

attended PTA meetings increased from 31% to nearly half of the parents,

47%.

Parents also checked

the students’ homework less during middle school than in elementary

school. The percentage of parents who checked homework at least once

per week dropped from 70% in elementary school down to 44% in middle

school. In particular, more than half of elementary school parents

(53%) checked homework every night, but that number decreased to 19%

during middle school. At the same time, the number of parents who

never checked their children’s homework also increased dramatically,

rising from 11% in elementary school to 39% in middle school.

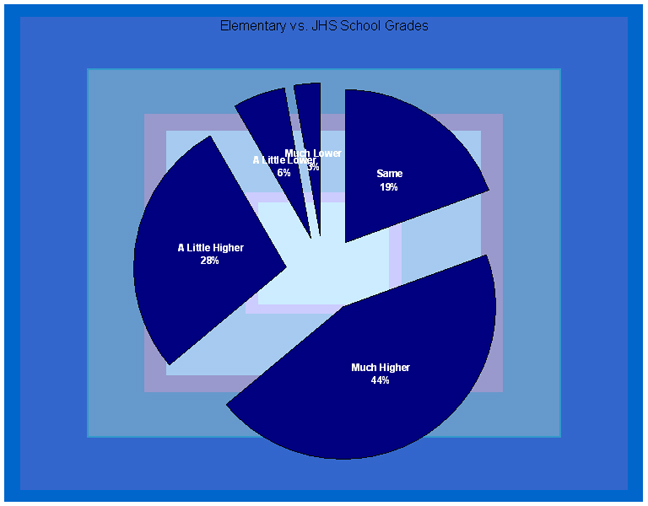

Finally, the majority

of the students surveyed achieved lower grades in middle school than

in elementary school, and many described the difference as significant.

Approximately 44% of the students surveyed reported having “much

higher” grades in elementary school, 28% reported receiving

“somewhat higher” grades in elementary school and 19%

reported their grades were essentially the same. (See Exhibit B).

Parent

Surveys

I conducted surveys of the parents soon after the student surveys

were completed. (See Exhibit C.) I conducted the surveys anonymously

at our first Parent-Teacher Night in early November. I chose that

venue because I wanted the opportunity to answer any questions about

the surveys because, although they were anonymous, they did ask personal

questions concerning the parents’ level of education and feelings

about education. The average turnout at the conference and the voluntary

nature of the survey resulted in less participation than expected.

However, the surveys I did receive revealed universally positive feelings

from parents about their past education and education completion levels

generally through high school. When questioned about their present

level on involvement (the choices were high, medium and low), no parent

reported anything less than a medium level of involvement. The majority

of the parents also indicated that their level of involvement had

not decreased since elementary school. While the surveys were informative

regarding the parents’ attitudes towards education, the sample

size was too small to provide any conclusive results. Were more surveys

completed by a representative sample of my student’s parents,

I believe the data may have been dramatically different in several

areas.

Communication

with Parents

On the first day of school, I sent a letter home to the parents of

all my students, introducing myself and outlining the basic curriculum

requirements and my expectations. The letter also stressed the importance

of their involvement and invited them to visit the classroom at any

time. Approximately 80 of 85 students returned letters signed by their

parents. Also, in conjunction with my principal, I also drafted a

letter on school letterhead addressed to employers that requested

they partner with our school in promoting parent involvement by granting

parents one paid ½ day off to visit the school. The letter

was advertised and distributed at PTA meetings throughout the year.

To my knowledge, no parent this year utilized the letter to facilitate

an in-school visit.

Throughout the

school year, I participated in many parent conferences, with many

of these occurring at our school’s Parent-Teacher Night when

the topic was the child’s latest report card. The vast majority

of the other conferences took place after myself or another teacher/administrator

had specifically requested that a particular parent come to the school

regarding an academic or disciplinary issue. Additionally, we also

mailed Progress Reports home to parents in the middle of each academic

marking period, specifically targeting those students in danger of

failing. The letters included teacher comments on the specific areas

in which the child was struggling and offered several suggestions

for improvement.

When questioned

about their level of involvement during conferences, parents generally

agreed that their children required more supervision. They revealed

several common reasons for their existing (or non-existing) level

of involvement: unfamiliarity/intimidation by the academic subject

matter, insecurity about how to provide assistance to their children,

time constraints due to commitments to jobs or younger children and

a general overestimation of their child’s responsibility level.

In order to combat

these problems, in several cases I first suggested that parents begin

monitoring their children’s homework on a regular basis. Based

on follow-up conversations with parents and students, most parents

were willing and able to increase the frequency of their homework

checking and assistance. In some cases the homework checks became

daily occurrences. For those students whose parents increased homework

monitoring, I generally found that the instances of missing or incomplete

assignments greatly decreased and class participation increased across

the board. Several students reported that they understood the material

more clearly and followed the lesson easily, which, in turn, increased

their willingness to volunteer during class discussions. The results

on classroom examinations were mixed. Most of the students improved

their performance on examinations, but only approximately ½

of the students who reported increased parent involvement demonstrated

passing grades of 80% or above on the examinations on a consistent

basis.

Several parents

did not remember the course material in any detail and expressed hesitation

in their ability to assist their children with their homework. For

them, I recommended (for approximately eight parents) that they start

having weekly conversations with their children about their material

being covered in their Social Studies class. The rationale was that

the child should be capable of providing an explanation of a topic

(i.e. Causes of the Civil War) that should at least sound reasonable

to the parent based on their general knowledge of the subject. If

the explanation did not sound plausible or the child was incapable

of explaining the topic, then the parent should recognize that the

child did not fully understand the topic. The parent should then recommend

that the child re-read the related chapter in the textbook and his/her

class notes and redo the homework. According to my follow-up conversations

with students, approximately 2 of the 8 parents attempted to utilize

this method, but it was not used on a consistent or long-term basis.

While this method sounded promising, the students suggested that perhaps

this expectation of parents was somewhat unrealistic.

Homework

via the Internet

In addition to our school’s administration establishing an Internet

homepage for the school as a method to increase contact with parents,

many teachers also created their own individual classroom homepages

as an additional communication tool. The main advantage of the Internet

classroom website that I explained to parents was that it empowered

them to monitor their children’s homework assignments independently

and eliminate to issue of children being dishonest or forgetful about

their homework. After introducing the Internet homework program, I

generally received positive responses from both the students and parents

that the website was informative and helpful. The program was effective

in reducing missed homework for absent students and those who failed

to record the assignment during class.

The website allows

teachers to monitor the number of visitors to the website by requesting

each visitor to identify themselves as a student, parent or ‘other’

before granting them access to the classroom homepage. Teachers can

also monitor which sections of the homepage visitors are frequenting,

for example Announcements, Assignments, etc. For the period from September

through May, the website recorded 1,581 visits to my classroom homepage,

comprised of 1,301 students, 255 parent visits and 25 others. The

majority of the student visits were to the Assignments page, while

the parents divided their attention between the general homepage with

104 visits and the Assignments page with 97 visits.

Parents reported

the site as helpful, when accessed, but also reported several shortcomings.

The primary concern was that a considerable percentage of my student’s

parents do not have Internet access at home. Also, although paperwork

detailing the program was distributed to both students and parents

on several occasions, many parents reported being unaware of the availability

of the website. Other reported problems were a general unfamiliarity

with Internet usage and the students’ failure to relay important

information concerning the website. While there were more than enough

parents who did have Internet access and usage experience to render

the program a success, too many families fell through the cracks to

make the plan a cure-all for solving homework problems.

CASE STUDY

In order to evaluate the potential effects of parent involvement in

the classroom, I followed the experience of one student who actually

had his parents visit the school and sit-in on several classes. As

stated earlier, despite my best efforts, enticing parents to sit-in

on classes proved to be the most difficult aspect of the research

I conducted. This student’s experience illustrates the problems

of instituting classroom visitations, their benefits when they do

occur, and their limitations.

My key student,

Dante (a fictional name for purposes of this study), is an average

Eighth grade student, in terms of standardized test scores, personality,

attitude and behavior. Dante started the year out on shaky academic

ground, achieving an 80% average in my Social Studies class, but failing

two others: Math and Science. I did not see his family on Parent-Teacher

Night, but that was not uncommon when a student achieved a good grade

in the class. Then, according to Dante, he began to ‘relax’

in my class. He began to miss homework assignments or not complete

them to the best of his ability. Dante also began to fail tests and

quizzes, some very badly. I followed the protocol of sending a Progress

Report to his home, alerting his family that he was in danger of failing

the class. His family did not respond to the Progress Report. He failed

the class for the marking period and his parents did not attend the

second Parent-Teacher Night in the middle of February. After conferencing

with Dante about his grades and seeing no tangible improvement, I

became concerned that he may fail for a second time in early March.

I called his home and left two messages requesting a conference regarding

his grades. The ensuing conference with Dante’s father and sister

revealed that not only had Dante been dishonest in responding to his

family’s questions concerning his academics, but had actually

hidden his second marking period report card from them.

After that meeting,

Dante’s adult sister began sitting-in on several of his classes

for approximately 4 days per week for two weeks and made 1-2 surprise

appearances thereafter. She also began checking and assisting Dante

with his homework on a nightly basis. Since that time I began to see

a dramatic improvement in Dante’s performance in my class. He

went from a student who generally did not participate in classroom

discussions to being the first hand up to answer questions. He also

began expressing very forceful and well-considered opinions and spurring

class discussions, even to the point where his classmates began to

tire of the sound of his voice. He stopped missing homework and the

quality of the written work greatly improved; he even began to type

several assignments. His grades on test and quizzes began to improve,

including several grades of 80% or better.

When I interviewed

Dante about the causes of his improvement, he stated that he was participating

more in class because his understanding the material improved since

he was reading the textbook more consistently and spending more time

on his homework. He credited his sister’s help with his homework

as a significant factor in this process. Dante also felt that his

focus and participation in class helped his test scores. He achieved

an average of 75% in my class for the fourth marking period and an

overall average of approximately 70% for the year. While he was certainly

capable of achieving a higher average, this represented a major improvement

over his position when the family intervention began.

However, Dante’s

results were not as encouraging in his other classes. While, his homework

improved in both his Math and Science classes, his test scores did

not. Dante claims that he has always struggled with Math, and his

Science projects were his undoing. Both his Math and Science teachers

confirmed his assessment. Interestingly, his Science teacher noted

that Dante’s sister only visited her class once or twice and

their conversations were infrequent. Based on this fact and Dante’s

own opinion of the impact of his sister’s visits, I concluded

that Dante focused his efforts most intently on those classes and

teachers that his sister focused on and paid less attention to the

others. For example, he did not attend the extra help sessions in

Mathematics and English that were available after-school and on weekends.

Unfortunately,

this tale does not have a storybook ending. Dante’s re-invention

as a student occurred too late to overcome the hole that he dug for

himself; while he saved himself in Social Studies, Dante was forced

to attend Summer School for not achieving an overall average of 65%

or better in his Math and Science classes. Thus, Dante’s sister’s

intervention, while certainly more dramatic than most teachers would

call for, is still instructive in its benefits. The intervention did

help Dante to improve his work ethic and academic performance, but

there was still room for improvement beyond the inspiration his family

could provide.

ANALYSIS

My data suggests that contrary to popular belief, urban parents do

get involved in their children’s education; but their level

of involvement decreases dramatically between the elementary school

and middle school years. This lack of involvement is directly hurting

the academic performance of middle school students, due their continuing

need for supervision and assistance with the material. Those factors,

combined with the additional distractions that middle school students

face with the onset of adolescence, have proved overwhelming for many

of them. Through the use of surveys and notes from parent communications,

three specific levels of problems with parental involvement are identified

and three strategies for overcoming these problems become apparent.

First, parents

noted a variety of causes for their decreased involvement in their

children’s academics at the middle school level: unfamiliarity

with the course material, time constraints, and simply allowing their

children more independence to manage their own schoolwork. Particularly

in the areas of PTA attendance and checking student’s homework,

schools and teachers must work to keep parents participating at a

high level by demonstrating to them that children need their parent’s

involvement more than ever at the Middle School level. This will require

more planning on the school and teacher’s part to develop effective

strategies for increasing parental involvement. The PTA allows parents

to stay abreast of events and programs that may be useful to their

families and allows casual contact with teachers and school administrators.

Involvement with homework can provide children with assistance for

troubling subjects and keep them aware that parents are maintaining

high expectation levels for time commitment, quality of work produced,

and ultimately grades. Dante’s case study illustrates that a

family member’s physical presence at the school combined with

home monitoring of work can have a powerful effect on a child’s

work ethic and results.

Second, Middle

School parents generally will increase their involvement if requested,

but their efforts are often more reactive then proactive. When I contacted

parents about crisis situations or they received a failing report

card, they were much more responsive than when I made general requests

for more involvement. In many of those cases, however, the response

came too late to salvage a passing grade for the student or to reverse

poor study habits. Parents also reported some hesitation in contacting

teachers for updates on their children without an invitation from

the teacher to do so. It is a reported fact that a sense of intimidation

of teachers by parents is still a barrier to effective communication,

particularly across differing cultures. It is imperative that teachers

convince parents that their assistance is essential at the beginning

of the school year, before bad habits manifest themselves in poor

grades. Teachers must also convince parents that dialogue between

them is welcome and will be beneficial for the students. In some cases,

letters home may not be enough; teachers and administrators must be

willing to take additional steps to initiate dialogue with parents.

The third problem

is that not all parents know how to effectively assist their children

academically. Many students are attempting to complete their homework

and studies, but require assistance, not monitoring. Several parents

reported that their unfamiliarity with the material made them hesitant

to assist their children with homework and studying. Given the fact

that the majority of parents today work full-time jobs, it is unrealistic

to expect them to review textbook material in their limited free time.

Teachers must offer assistance to parents by devising creative assignments

and study methods in order to make it easier for parents to involve

themselves in the course material. While this is not feasible to accomplish

on an everyday basis, occasional parent-oriented assignments would

be very useful in involving parents in homework in a meaningful way.

When parents feel they understand the material, they are much more

willing to spend time assisting students with homework and discussing

the material in general.

POLICY

IMPLICATIONS

While this a small sample to parents and students, the research has

shown that parent involvement decreases between elementary and middle

school, but middle school students perform at a higher academic level

when their parents are involved in their schoolwork. Therefore, in

order to increase that involvement there must be a concerted effort

at the classroom level, the school level and the district level to

talk to parents about what level of involvement their children need

them to provide.

Classroom

Level

Classroom teachers must increase their efforts to initiate and maintain

contact and involvement from parents. Teachers must write introductory

letters to parents, maintain an open-door visitation policy, and continue

to reach out to both responsive and unresponsive parents. Reports

that include good academic news may assist in promoting more cooperative

relationships and increased dialogue between teachers and parents.

Teachers must also find methods to get parents involved in students’

homework beyond simply checking to see that it is done. One method

may be to initiate several low-maintenance joint student-parent assignments

that serve to facilitate family discussions and build parents’

confidence in their abilities to understand the material and assist

their children.

School

Level

At the school level, administrators must dedicate time and resources

to promoting parental involvement. Methods such a parent orientation

sessions where expectations for involvement are clearly delineated

and explained, have been found to be helpful. Several schools have

achieved increases in participation through programs/changes designed

in response to parents’ suggestions in school questionnaires.

Schools must also

support the growth of teachers in the area of developing parent relationships.

That starts with dedicating planning time, such as professional development

sessions, to sharing previously effective methods for increasing involvement,

as well as brainstorming new and creative techniques. Teachers, especially

new teachers, cannot be left to themselves to devise effective strategies

for involvement. Additionally, schools must assist teachers in communicating

with unresponsive parents. Administrators must be willing to make

phone calls to parents and assign other support staff to assist in

those efforts. One area for improvement in that regard is increasing

the availability of translators to facilitate communication with families

that do not speak English as their primary language.

District

Level

School districts must also allocate resources to conducting research

and developing effective strategies for improving parental involvement.

This may require consultations with experts in the field, training

for local superintendents and principals, and funding for new initiatives

as well as existing programs that have been effective in other jurisdictions.

School districts must also be willing to consult with local politicians,

community leaders and parents to discuss their concerns and receive

their input on potential solutions. Administrators can no longer lament

the absence of parental involvement without making tangible efforts

to include them as a valuable part of the educational experience.

The need for improvement

in our schools has been well documented over recent years and changes

have been made that appear initially to be experiencing some success.

However, all of our problems cannot be solved by legislation or by

well-intentioned and dedicated professionals working in a vacuum.

Only through discussion and cooperation between all of the various

constituencies in the community will the challenges to parental involvement

be fully understood and effective practices for change be instituted.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Henderson,

A.T. and Berla, N., A New Generation of Evidence: The Family is

Critical to Student Achievement. Washington, D.C., National Committee

for Citizens in Education.

2. Sanders, Mavis

and Epstein, Joyce (1998). School-Family-Community Partnerships

in Middle and High Schools. Center for Research on the Education

of Students Placed At Risk.

3. Steinberg,

Laurence (1996). Beyond the Classroom: Why School Reform has Failed

and What Parents Need to Do. New York: Simon & Schuster.

4. Bogenschneider,

Karen and Johnson, Carol (2004). Family Involvement in Education:

How Important Is It? What Can Legislators Do? Madison, W.I.,

University of Wisconsin Center for Excellence in Family Studies.

5. Henderson,

A.T. and Mapp, K.L. (2002). A New Wave of Evidence: The Impact

of School, Family and Community Connections on Student Achievement. Austin, TX. National Center for Family and Community Connections with

Schools

EXHIBIT A

STUDENT SURVEY

The purpose of

this survey is to measure levels of parent involvement in elementary

school and middle school. Please choose the answer that is the closest

to your opinion.

_______ 1. How

often did your parent attend PTA meetings when you were in elementary

school?

a. Frequently

b. Occasionally (2-3 per year)

c. Once or twice

d. Never

_______ 2. How

often did your parent speak your teachers in elementary school?

a. Very often

b. Parent-teacher nights

c. When teachers called

d. Not at all

_______ 3. How

often did your parents check your homework per month in elementary

school?

a. Almost

every night

b. Once per week

c. Every 2 weeks

d. Never

_______ 4. How

often did your parents help you with your homework per month in elementary

school?

a. Almost

every night

b. Once per week

c. Every 2 weeks

d. Never

_______ 5. Did

your parent ever sit-in on any of your classes in elementary school?

a. Yes b.

No

_______ 6. How

were your grades in elementary school compared to junior high school?

a. The same

b. Much higher

c. A bit higher

d. A bit lower

e. Much lower

_______ 7. How

much do you believe your parent’s involvement affected your

grades in elementary school?

a. Major

effect

b. Minor effect

c. No effect

_______ 8. How

often does your parent attend PTA meetings in middle school?

a. Frequently

b. Occasionally (2-3 per year)

c. Once or twice

d. Never

_______ 9. How

often does your parent speak your teachers in middle school?

a. Very often

b. Parent-teacher nights

c. When teachers call

d. Not at all

_______ 10. How

often does your parents check your homework per month in middle school?

a. Almost

every night

b. Once per week

c. Every 2 weeks

d. Never

_______ 11. How

often do your parents help you with your homework per month in middle

school?

a. Almost

every night

b. Once per week

c. Every 2 weeks

d. Never

_______ 12. How

aware are your parents of the topics you are covering in your major

classes (ex. Civil War in social studies class)?

a. Very aware

b. They know about 1-2 classes

c. They ask me occasionally

d. Not aware

EXHIBIT

B

EXHIBIT

C

PARENT

SURVEY

This survey is

part of a research study being conducted on Parents, Children and

their Schools. The purpose of the survey is to examine parents’

perspectives on schools and their children’s educational experiences.

The children have already completed a survey with similar questions.

Please answer as completely and accurately as possible. The survey

is anonymous, so please do not write

your name on it. Thanks for your cooperation.

1. What are your

feelings about your own educational experience?

2. What is highest

academic grade completed in your household?

3. What methods do you use to monitor your child’s academic

progress in school?

4. How would you

describe your child’s attitude towards school and education?

5. How would you

describe your level of involvement in your child’s school (ex.

homework, test preparation, teacher contact, PTA, etc.) – High,

Medium or Low. Has it always been at this level? |