Jeremy

Copeland and Jen Dryer

School of the Future—Manhattan

Research

Question

How do racial and cultural tensions between students impact classroom

dynamics?

How can teachers help students break down barriers formed by differences

in race and culture?

Rationale

“Yo,

I don’t wanna sit next to Ariella. She’s racist.”

“Yeah, she’s a nigger hater.”

These comments

exploded into our respective ninth grade Humanities and Spanish classrooms

one week in November of 2003. A verbal melee ensued and all teaching

for the remainder of the class was thrown out the window in an attempt

to address this palpable racial and cultural tension that had been

brewing in this one class since the beginning of the year. It started

with comments as early as September, such as, “Hey, everybody’s

favorite Puerto Rican is here!” and “Why do you think

I’m rich? Because I’m White?” (The answer was “Yes”).

If integration

is the goal of the landmark case Brown v. Board of Ed., then School

of the Future (SOF) is its utopian vision. A small public school in

Manhattan’s tony Grammercy Park, SOF serves students in grades

6-12 from all five boroughs of New York City. SOF is part of New York

City’s Region 9 schools, and was formerly part of Manhattan’s

Community School District 2, renowned as one of NYC’s wealthiest

and highest performing districts, and one that invests time and finances

in extensive professional development for teachers and administrators.

Although most students reside in District 2, which extends from Chinatown

to the Upper East Side and from Greenwich Village to 59th Street on

the West Side, many come from other parts of the city. Most SOF students

stay from middle through high school, although some leave and are

replaced by new students who apply and are interviewed before earning

acceptance to the school.

SOF’s classes

usually top off at 25 students, a class size cap much lower than its

counterparts in NYC. With approximately 600 students in seven grades,

SOF is very diverse, in terms of race/culture, socioeconomics, physical

ability and academic ability, and has a strong Inclusion program for

special needs students who are mainstreamed into the classroom. Students

at SOF travel from class to class in cohorts, so that, with the exception

of high school foreign language, in which their class is split in

half among French and Spanish and combined with half of another class,

they stay with the same class groupings all day. These class groupings

are generally given names by the team of teachers teaching them. The

class in which the “racial” outbursts described briefly

above was aptly named “Fire,” as part of the four classes

in the 9th grade, named Earth, Wind, Fire and Water.

The approximate

ethnic breakdown of the student population at SOF is 38% White, 22%

Black, 25% Latino, 15% Asian, and 10% other (including South Asian,

West Indian and Middle Eastern/Arab). Approximately 40% of SOF students

qualify for free lunch, while other students have vacation homes outside

the metropolitan area or travel extensively with their families. Then,

of course, there are many whose socioeconomic standing falls somewhere

in the middle.

Whereas many

public schools in NYC seem to have become resegregated (Southern Poverty

Law Center), SOF is committed to maintaining its diversity, which

is central to its basic philosophy. As a result of the small class

size, extensive time in the same class groupings, and collaborative

work environment, students at SOF know each other quite well and tend

to interact with others of different backgrounds regularly. However,

although it would seem that all these structures in place at SOF would

foster a genuine sense of tolerance and collegiality of students of

different racial and ethnic backgrounds, we soon realized that diversity

may not be enough.

Our experiences

with this one particular class cohort (described above), “Fire,”

drove home how crucial it was to step back and take stock of students’

attitudes towards and perceptions of their own and others’ race

and culture, and how this impacted the dynamics of the classroom.

It also drove home the fact that we needed to implement some type

of intervention in order to reestablish an environment in which students

could feel safe to learn and in which we could be able to effectively

teach our students the required curriculum. We further realized that,

as educators, we were never really trained how to deal with racial

tensions in the classroom and how to act before those tensions become

real obstacles to learning. This study of our students’ assumptions

about and attitudes towards others of different cultural backgrounds

was just as important to our own development as educators as it was

to our students’ development as human beings living in a multicultural

world.

Research,

Data & Analysis

We collected data through various surveys of students in the class

and personal journal entries recording our observations. We began

by collecting baseline data around our students’ perceptions

about race and culture, and their comfort level communicating in meaningful

ways across “cultural borders.” We also asked students

to name four to five classmates they worked with best and four to

five with whom they were least comfortable working with, and why.

The data collected

was analyzed in varied ways. The students’ work partner preferences

were collected twice, once in February and once in June, and were

analyzed using a sociogram, coding students in the class by both gender

and cultural background. We assessed whom students wanted to work

with and did not want to work with, using both gender and ethnicity

as markers. We chose to separate gender from ethnicity to see if there

was any correlation along gender and racial/ethnic background. Twenty-two

students, out of 25 in the class, completed the first seating preference

survey, and nineteen completed the second survey in June, as the result

of three absences and three students who had moved away or gone on

vacation before the end of the year. Twenty-four students completed

surveys on their perception of and attitudes toward race and culture

in the school and classroom.

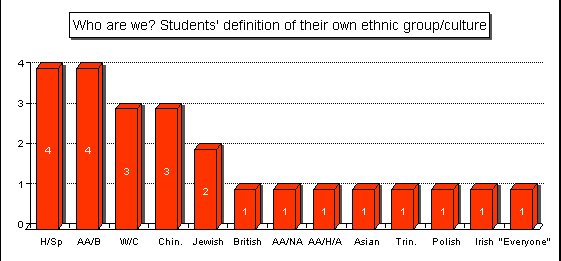

The data collected

was surprising at times and gave a great deal of insight into the

way that students saw and understood themselves and their colleagues.

There was a distinct disparity between the way students defined others

in the classroom and the way they defined their own cultural background.

Most students tended to see others in “cultural clumps,”

such as “Caucasian” or “Black,” whereas when

they self defined, they tended to be more ethnically specific, describing

themselves, for example, as “Polish” or “Jamaican.”

This idea is supported by research, such as that by Laurie Olsen,

which suggests that school is the place that “racializes”

white students. Based on their survey responses, students also seemed

to feel more culturally isolated in the classroom than they did in

the school as a whole, which, we surmised, contributed to the marked

cultural tension in the classroom.

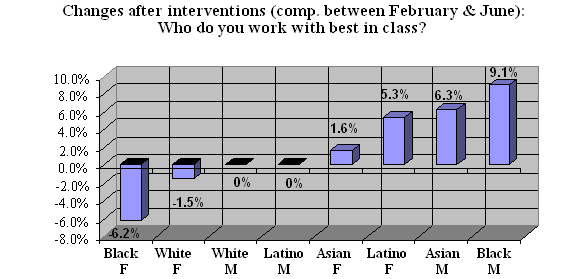

Students’

work partner preferences similarly yielded interesting results. When

noting why Black and Latino males were unfavorable work partners,

many reasoned that they “goofed off” or “fooled

around” too much. Some students of color used similar racially

coded language, noting that White students were “annoying”

or that “we just don’t get along.” After our interventions,

we repeated this survey, and there were some significant changes,

along with a much lower incident of such racially coded language.

The most significant change occurred among Black males, whose popularity

as workers rose 9.2%, which was significantly higher than their representation

in the class. Asian males also gained 6.3% in their popularity, over

100% increase from the February survey. In least popular work partners,

the June survey results were much more ethnically dispersed, as it

became clear that students were less prone to use cultural background

to determine work partner choices.

Students’

work partner preferences

Policy

Implications

- Teachers need

professional development relating to their own assumptions and practices

around issues of race/culture.

- Curriculum

pertaining to cultural and racial border crossing should be imbedded

in public education (SS or advisory classes), whether in a diverse

or more homogenous environment.

- New York City

DoE should actively engage strategies to build a more diverse teaching

force.

|