What Matters Most-Improving Student Achievement | Getting Real and Getting Smart: A Report from the National Teacher Policy Institute | Literacy

What Our Action Research Tells Us About How To Improve Literacy

By MetLife Fellows, Teachers Network Policy Institute

OVERVIEW

A significant number of students enter middle school without the ability to read and understand their required coursework. Thirty-seven percent of fourth-grade students fall “below basic” in reading, according to the 2000 NAEP Reading Report Card for the United States. Seventy-four percent of children who are poor readers in the third grade remain poor readers in the ninth grade. As teachers, we know that there are a number of reasons for this problem including:

- Inadequate exposure to literacy conventions and literacy instruction during early childhood

- Inadequate preservice and in-service teacher education regarding the teaching of reading

- Transience—migrant children, military dependents, and children of poverty move frequently, disrupting their education and making it difficult for them to obtain cohesive, connected reading instruction

- Immigration—children who enter American schools after the early childhood years may be lacking basic literacy in their own language, which negatively impacts on their acquisition of English language skills

- Low parental education levels and/or lack of parental knowledge about how necessary it is to talk to children, read to children, and explain to children.

DEFINITIONS

Literacy encompasses communication through reading, writing, speaking and listening. The four are interrelated, so development in one impacts development in the other three.

Early reading or beginning reading is comprised of skills and strategies that lay a foundation for deeper understanding and analysis. Some of these are: awareness of letters and sounds (phonics), strategies for figuring out words, fluency, accuracy, and comprehension.

Intervention refers to programs to help students who need extra help. Examples of intervention are summer school, after school, Saturday classes, special classes during the school day, and tutoring. |

PRINCIPLES

- Literacy is increasingly necessary in the Information Age.

- We must recognize that the problem of adolescent illiteracy exists.

- High stakes testing will not reduce illiteracy.

- Not everyone learns to read in the same way.

- Literacy development begins at birth.

- Many students enter the American educational system after early childhood, lacking basic literacy skills.

- Partnerships between home and school are crucial to literacy development.

- Regardless of job titles, all teachers are teachers of reading,

.

|

Universal literacy will require attention in four areas:

-

pre-service teacher education and ongoing teacher professional development

-

intervention based on individual children’s needs

-

working with students at their level and providing appropriate resources

-

home-school connections, specifically working with parents on how to create literate environments and encourage children to become literate.

Recommendation 1: Professional development in reading instruction, which includes decoding, fluency, accuracy, and comprehension, must be part of the preservice education and on-going professional development of ALL teachers. There is a need to articulate a continuous flow of knowledge from kindergarten through high school so all students

develop the skills they need to be successful in school.

Preservice: Prior to graduating, teacher candidates, at all grade levels and subjects, will demonstrate competence in teaching reading. Teachers who work with student teachers/interns

should be selected based on a strong ability to teach reading.

In-service: All new teachers should receive professional development and coaching that focuses on early reading skills. Studies by Jane Fung (1999), Karen Kuntsman (1999), and Sarah Picard (2001) show how valuable it is for new teachers to be able to work in this way with other more experienced teachers:

-

Jane Fung’s research focused on 9 new teachers who joined her in-school network for beginning teachers. Among its successes, the network was instrumental in helping new teachers acquire a deeper understanding of state language arts standards and subject matter knowledge.

-

Karen Kuntsman also investigated the effects of teacher networks on new teachers’ practice. The participating teachers reported greater confidence with teaching writing.

Students’ written work showed improvement .

-

Sarah Picard documented the impact of regular, after-school meetings with an experienced teacher during which they focused on student progress in reading. By June, 93% of Picard’s second grade students – 80% of whom were ESL students -- were reading at or above grade

level.

Ongoing professional development should be formulated in response to needs articulated by teachers. Marika Paez (2002) studied weekly professional development meetings focused on literacy instruction.

According to Paez, participating in weekly professional development meetings with a master teacher and fellow colleagues:

-

increased her knowledge of and ability to articulate the “Big Ideas” about how students learn to read and write

-

gave her the opportunity to see instructional strategies in action which increased

her confidence and competence in implementing more focused and explicit instruction

-

provided her with a supportive environment in which to navigate a sometimes overwhelming transformation in

her instruction

These studies suggest that the investment in sustained professional development focused on literacy pays off in terms of improved instructional practice and better student learning. School districts might want to consider hiring literacy coaches to work with teachers across all content areas and providing release time for teachers to attend training sessions and observe successful teachers.

Derric R. Borrero & Cynthia del Pino (1999) found that teaching reading and writing along with science experiments helped students meet the NYC language arts standards and pass the reading test while enhancing their understandings of the science curriculum:

Thirty-four 3rd graders studied the animal of their choice using fiction and non-fiction books along with software. The classroom was equipped with a computer, a library full of animal books of different genres, and several terrarium tanks. Using the terrariums, the students studied the animals and rebuilt their habitats. By experimenting with various habitat arrangements, the children learned how to use the scientific process. Even in simple cases, like water leakage from a tank, students set up experiments to find the best solution. All of their information was recorded in science journals. The journals were used to maintain all of the data being collected and later guided the students’ final pieces of writing. These were then published using the class computer.

At the end of the program, all of the children understood the difference between each of the animal family groups. They could follow the scientific process to set up any experiment. Students constructed dioramas that depicted the habitat of the animal that they had studied. Each child produced a fact book about the animal and a book report in which they compared the manner in which the animal was described in the book with the facts that they had learned about their animal. They also wrote stories using the animal studied as the main character. Finally, they wrote a narrative procedure explaining how to take care of a pet or how to make a diorama of their animal’s habitat. Twenty-eight of the 34 students met the English Language Arts Standards at a satisfactory level.

At the high school level, Dhakkar (2001), a social studies teacher successfully taught early reading skills (vocabulary, finding the main idea of a passage, using context to work out word meanings) as she helped her students prepare for the U. S. History and Government Regents tests. Kathy

Blackwood (1999), a mathematics teacher who used journal writing to help her students understand complex math concepts, wrote:

By far the greatest value to me as a teacher was being able to understand the students thinking about a concept, especially when it was leading them to incorrect conclusions. I often was able to reteach or adjust a lesson and clarify problems in student thinking. The hour or so that it took to read and comment on their work was well worth the investment. While reading, I was making decisions about what to do next, so lessons were being planned at the same time.

Immersing children in literacy activities as they study in the content

areas ensures that they will develop literacy skills and become knowledgeable in all content areas.

Recommendation 2: Students who are reading below grade level must receive intervention to help them acquire beginning reading skills. This intervention should be based on each child’s individual needs and should be multi-dimensional -- not confined by a scripted curriculum or a rigid set of instructional strategies. Pre- and in-service literacy training for teachers who work with illiterate adolescents

should include strategies and methods for addressing the many unique needs of students with a variety of backgrounds: those who were not in school in the United States or anywhere at all prior to junior high or high school; those who have learning disabilities; those who did not learn to read in the traditional classroom.

In her study of high school literacy, Carol Tureski (1999) found that 50% of NYC literacy teachers surveyed reported that phonics and word games were powerful strategies for increasing the literacy levels of English-language learners.

Tal Abbady (1999), a NYC teacher, found that a small class size enabled her to provide small group and individualized instruction as students prepared for end-of-course tests.

In Santa Barbara County, skilled teachers brought second language learners from the bottom of a cohort to the top as a result of one-on-one and small group intervention (Paloutzian, 1999; Wiezorek, 1999, 2001).

In Caspar, Wyoming, Felbeck (2002) found that a small class of at-risk seventh and eighth graders increased their reading scores in an all-day reading program designed for older children who have experienced reading failure. In the fall, 16 students were labeled at risk; by the spring, only 6 students retained that label.

These studies suggest that districts and schools should evaluate their current intervention programs to make sure that intervention teachers are skilled in teaching reading and that students are referred for intervention by their classroom teachers

on the basis of broad range of assessments rather than test scores alone. Intervention classes should be small

(15 at the most) to allow for individual differences.

Recommendation 3: Teachers should work with students at their level by providing appropriate resources.

They need to increase the number, quality, and variety of books available in classroom and school libraries. The titles available should reflect the interests and needs of the student population.

Joe Gottschalk (2001) studied ESL learners. He found that drills in phonics and spelling were not enough to support emerging literacy. Students needed practice in speaking and listening. He engaged them in small group work where they could practice familiar dialogue and work with more sophisticated readers and writers. He writes,

Reading is social because it involves communication with others. Children learn to read by interacting with other people. When readers construct meaning they bring their background knowledge and experiences to the text.

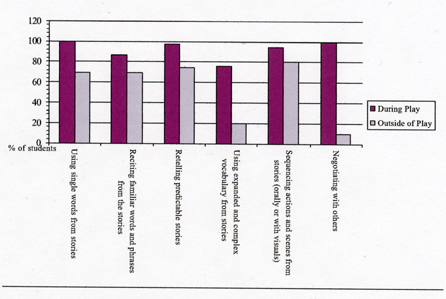

Like Gottschalk, Susan Brown (2001) and Susan Courtney (1999) found that going beyond pencil, paper, and drill work enabled expansive growth of literacy skills. Brown and Courtney focused on children’s play – Brown looked at block play, Courtney at a variety of play activities. Susan Courtney concludes her study writing, “Play is a necessary and important component where students extend and refine the language they are learning and using.”

Percent

of Student Initiated Literacy Activities During and Outside of Play

Ron Foster (1999) studied writing prompts in a first grade classroom. He found that choice was extremely important to first graders’ sense of competence as writers. He found that by giving students a balance of teacher-assigned and self-selected topics and picture prompts, students did better on standardized tests. “The evidence,” he writes, “indicates that educators need to move away from an all-or-nothing approach and provide multiple options for students’ writing topics.”

Matt Wayne (1999) Denise Watson (2001), and Carol Tureski (2001): Three NYC teachers found that infusing their classrooms with quality literature and allowing student choice among reading materials improved students’ higher-level thinking skills and was a factor in improved reading scores.

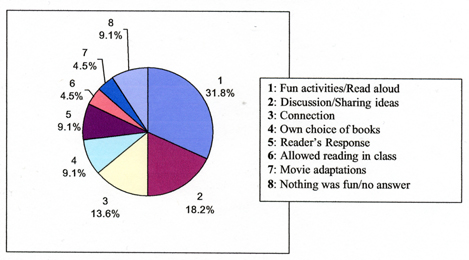

Mary Anne Love, Loren Herrington, & Carol Robinson (2002) found that even advanced readers need careful attention. In studying a group of middle school readers, they found that teachers have a powerful impact on kids’ sense of self and on their reading selection.

The following graph shows what they learned

when they asked students how have teachers made reading enjoyable?

Student's

Responses to the Question "How Do Teachers Make Reading Enjoyable?"

Gail Ritchie (2002) found that connecting author studies to subject area studies such as science, mathematics, or social studies, led to increased student achievement in reading, writing, and the content areas. In a review of research related to storybook reading in elementary school classrooms, Ritchie (2002) found that students especially benefit from small group, dialogic-style storybook reading experiences.

Recommendation 4: Teachers should meet individually with parents to discuss their children’s reading. Parents need information on how to support reading at home. Parents need to realize the importance of regular school attendance for student success.

Lara Goldstone (1999, 2000) documented that bilingual Chinese sixth-graders met reading and speaking standards after their teacher informed parents

about how they could support the standards at home.

Sandra Bravo (2002): studied the ways in which a family literacy program made learning opportunities accessible to ESL parents and, through them, their children. Bravo highlights the importance of parent involvement in children’s learning.

Ellen Schwartz (1999), a middle school teacher from Santa Barbara County, CA, used an instructional tool – the reading log – to examine how monitored reading at home can influence reading improvement among English Language Learners. In her study, she looked at how parental involvement influenced reading improvement for Hispanic students designated as limited English proficient. Pre- and post-reading tests were administered and almost all the students showed dramatic improvement – some more than 2 ½ years during the 9-month period spanning September to May.

These studies lead us to amplify our recommendation by suggesting that school districts set aside enough time on the school calendar for teachers to hold meaningful conferences with each parent. Middle school teachers may need two entire

days to reach all parents. We also suggest that schools develop methods to support and ensure regular attendance. It would be helpful to all concerned if standards were translated into the primary languages of all stakeholders. Finally, we suggest that teachers be prepared

in developing and delivering meaningful literacy workshops for parents.

Feedback.? Please e-mail

us. |